High-speed CMOS sensors provide better images

Conventional CMOS image sensors are not suitable for low-light applications such as fluorescence, since large pixels arranged in a matrix do not support high readout speeds. A new optoelectronic component speeds up this process. It has already been patented.

CMOS image sensors have long since been the solution of choice for digital photography. They are much cheaper to produce than existing sensors, and they are also superior in terms of power consumption and handling. Consequently, leading manufacturers of cell-phone and digital cameras fit CMOS chips in their products almost without exception. This not only reduces the demands made of the battery, it also makes increasingly smaller cameras possible.

Yet these optical semiconductor chips are now reaching their limits: while miniaturization in consumer electronics is leading to increasingly smaller pixels around 1 micrometer across, certain applications require larger pixels in excess of 10 micrometers. Particularly in areas where only minimal light is available, such as in X-ray photography or in astronomy, having a larger pixel area compensates for the lack of light. Pinned photodiodes (PPD) are used to convert the light signals into electrical pulses. These optoelectric components are crucial for image processing and are built into the CMOS chips. “Yet when the pixels exceed a certain size, the PPDs have a speed problem”, explains Werner Brockherde, head of department at the Fraunhofer Institute for Microelectronic Circuits and Systems IMS. Low-light applications tend to call for high image rates. “But the readout speed using PPD is too low”, says Brockherde.

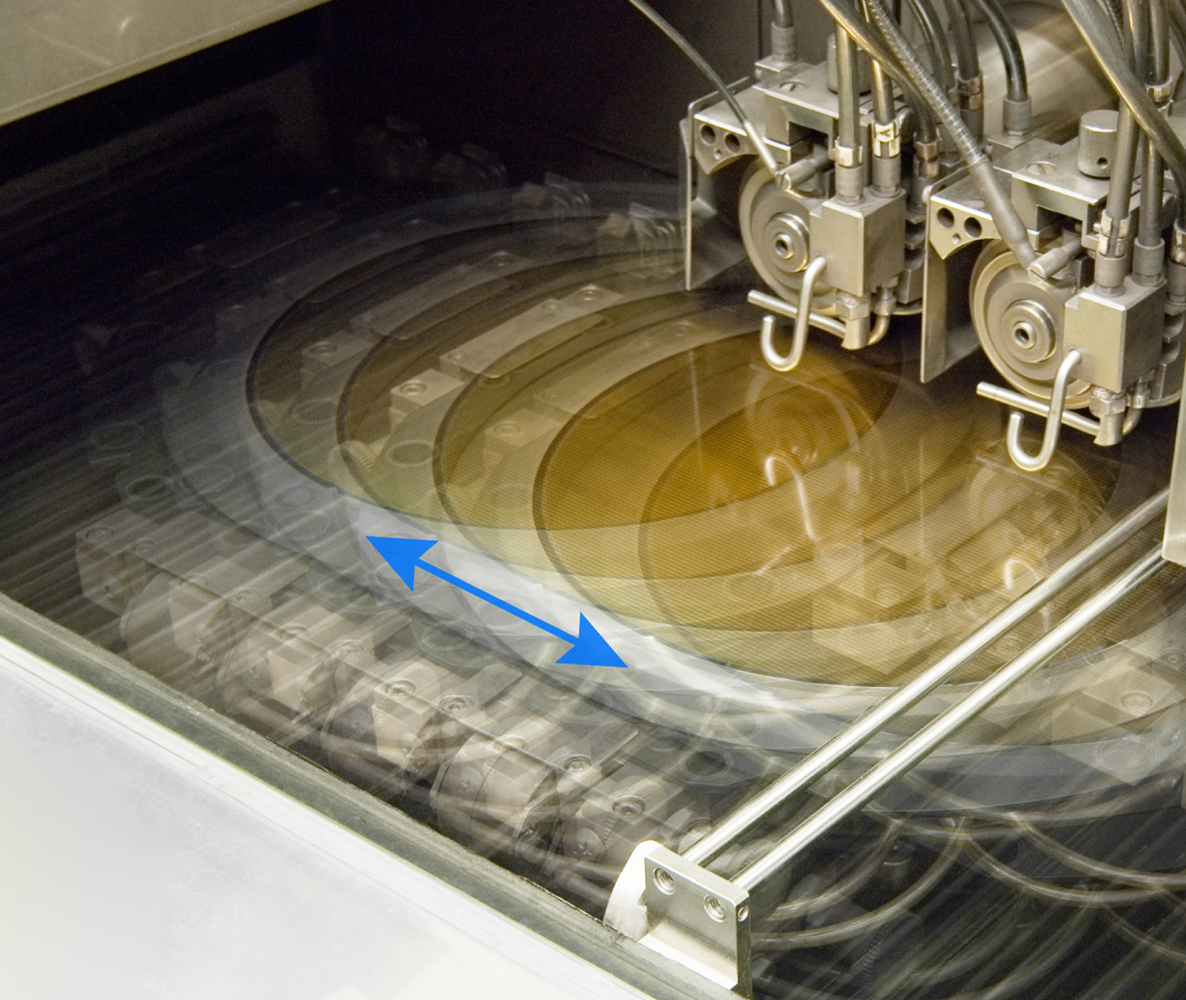

The Fraunhofer researchers have now come up with a solution to this problem – it is unique and has already been patented. The scientists have developed a new optoelectronic component, the lateral drift field photodetector (LDPD). “In this component, the charge carriers generated by the incident light move at high speed to the readout node,” explains the researcher. With the PPD the electrons simply diffuse to the exit; a comparatively slow process but which is sufficient for many applications. “But by integrating an internal electric field into the photoactive region of the component, we have managed to accelerate this process by a factor of up to a hundred.”

To produce the new component, the Fraunhofer researchers improved upon the currently available CMOS chip manufacturing process based on the 0.35 m standard: “The additional LDPD component must not be allowed to impair the properties of the other components,” says Brockherde. Using simulation calculations the experts managed to meet these requirements – and a prototype of the new high-speed CMOS image sensors is already available. “We expect to get approval for series production next year,” says Brockherde.

The high-speed CMOS sensors are ideal candidates for applications that require large pixels and a high readout speed: astronomy, spectroscopy or state-of-the-art X-ray photography are among the potential applications. But the sensors are also ideally suited for use as 3-D sensors based on the time-of-flight process, whereby light sources emit short pulses that are reflected by the objects. The time-of-flight of the reflected light is then recorded by a sensor and used to create a fully-fledged 3-D image. This technology is a compelling proposition for applications such as crash protection, as the sensors can precisely record their environment in three dimensions. The Fraunhofer researchers have already developed this kind of area sensor based on the unique pixel configuration for TriDiCam GmbH.

It takes a special kind of microlens to ensure that the light rays are focused precisely on the sensor. In order to manufacture the lenses, the Fraunhofer engineers first had to calculate the optimum shape by means of simulations. To eliminate external factors, it had to be ensured that the lens was capable of clearly separating the right and left visual channels. In concrete terms this means ensuring that no more than five percent of the energy from one light ray is captured by the line of sensors serving the other channel – in signal transmission this is known as crosstalk.